My experience with the Advanced Specialist Diploma in Diagnostic Cytology

Sue Smith, Advanced Practitioner, Cellular Pathology Department, Path Links Pathology Services

My journey with the Advanced Specialist Diploma (ASD) in Diagnostic Cytology (DC) began back in 2017 when the Lead Consultant Pathologist suggested I consider taking the qualification to further my knowledge and skills in cytology. I had been independently reporting negative DC for a number of years and jumped at the opportunity to learn more. I set about investigating the requirements of the portfolio and exam and started formally undertaking the qualification in early 2018.

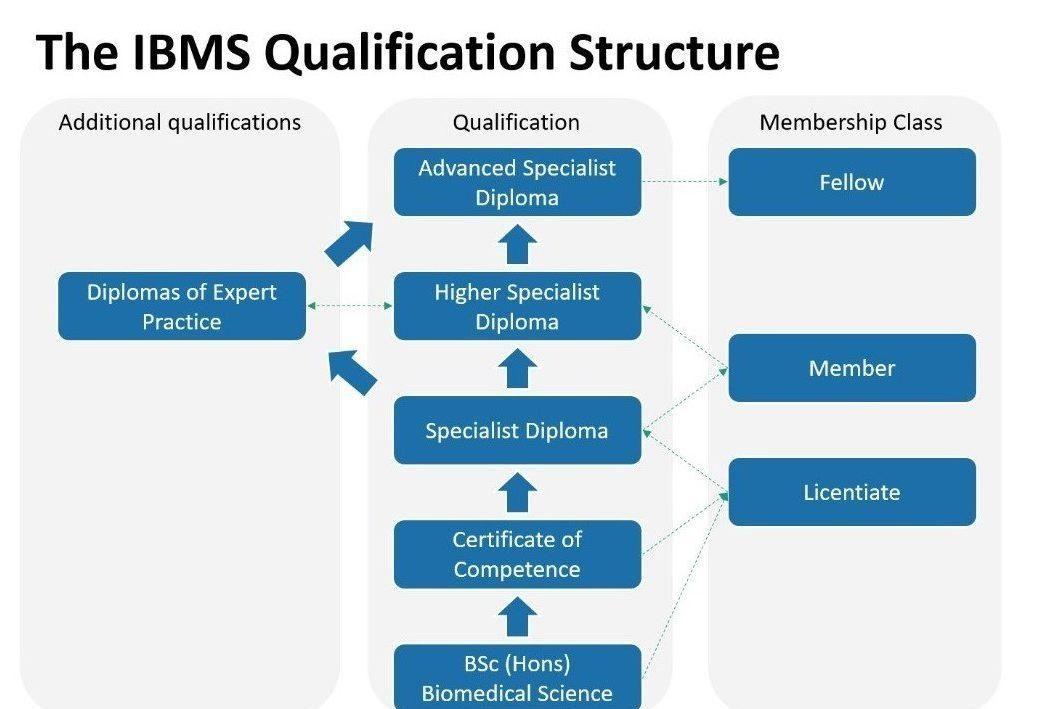

The ASD is the highest level qualification set by the Institute of Biomedical Science (IBMS), conjoint with the Royal College of Pathologists (RCPath), with the purpose of recognising significant skills and expertise in Biomedical Scientists. The qualifications are available in multiple disciplines including Diagnostic Cytology and Cervical Cytology and build upon Diplomas of Expert Practice (DEP) and the Higher Specialist Diploma.

Portfolio of evidence

At the time I commenced the qualification assessment was by portfolio of evidence, which if deemed satisfactory was followed by a written and a practical exam. As an entry requirement for the ASD is the completion of the DEP, I felt reasonably confident that I could fulfil the expectations. The format of the portfolio was familiar, requiring a record of a minimum number of cases, case reviews and case studies, together with in house assessments, CPD records, audits and reflection.

What did the portfolio entail?

For me, the surprise was the sheer quantity of work, much more than I had previously completed for the DEP. Because of this, organisation was paramount. The case logs were time consuming; although I already recorded details of the specimens I looked at, I needed to include outcomes for 50% as a minimum. It is important to remember that the key throughout everything is ultimately the patient and candidates need to demonstrate knowledge of the differential diagnoses, impact and clinical outcome. I gathered a plethora of information from my MDT attendance which I found invaluable and really helped my understanding of the wider clinical picture. Support from colleagues and managers was required, and much appreciated, as was input from colleagues in other departments and hospitals. To complete case reviews and assess my progress a great deal of involvement was required from Pathologists and not forgetting my supportive family. Thankfully all the time and effort was rewarded when my portfolio was deemed to be at a sufficient standard to progress through to the written and practical exams.

Exam preparations

I had a few months after confirmation of my successful portfolio to prepare for the exams. At this time, pre-Covid-19, both the written and practical exams were held at the North of England Pathology and Screening Education Centre (NEPSEC), with the written exam taking place in the afternoon, followed by the two practical papers the following day. Much of the research, MDT attendance and evidence gathering for the portfolio provided resources for the exams. I continued to attend as many webinars and presentations as I could to keep up to date and found valuable resources on various websites, including the British Association of Cytopathology.

I found little information regarding mock exams or practice papers online and I felt a little in the dark about the breadth of material which would be included in the assessments. When I heard about the first pre-exam course for the ASD, run at NEPSEC, I jumped at the chance to attend. I had found these courses really useful for the DEP and also, many years prior, for the cervical cytology screening exam, and again it proved to be well worth attending. I found it particularly useful to look at a variety of preparation types. It had been a long time since I had screened a Thinprep or Surepath slide, so practice was definitely required.

Over the following months I did lots and lots of reading and tried to write some practice questions for a mock exam. I soon realised how little writing I did on a day to day basis and struggled not to get writer’s cramp after just 10 minutes! The pre-exam course had highlighted just how broad the written exam could be, but the depth and time pressure was still a little unknown.

The day of the written exam soon arrived and I felt reasonably well prepared when I first sat down, ready to turn over the paper. I was incredibly nervous, hopeful that I had enough knowledge and that words would flow when I started answering the questions. Well, I managed to finish, but really did not feel I had performed my best. The written exam requires the candidate to answer 4 questions out of 6 in 100 minutes. It covers all aspects of DC, not limited to the sample types included in the portfolio, however I did underestimate the sheer variety of questions.

I found the first exam overwhelming and emotionally draining. At this point I did realise I was wholly underprepared. There were gaps in my knowledge; I might have been able to write a sentence or two about some subjects, but not a number of paragraphs. I also found the volume of writing a challenge, as anticipated, especially on broad subjects such as preparation. I needed to try to recover from my disappointment of this written exam and get ready for the microscopy the following day. Nerves and apprehension were now huge.

After a rather broken night’s sleep I joined my fellow candidates to sit the practical exam papers, having set up my microscope the previous day. There are two practical elements to the qualification; at this time they comprised one paper of 12 short cases taking 6 minutes per case and a second paper of 5 long cases at 20 minutes each. The marking criteria were similar to those of the DEP:

Correct answer – 5 points

Correct with additional information – 6 points, rarely 7 points (exceptional)

Incorrect answer – 3 points

An average of 5 points was required to pass. I knew it would be difficult to gather additional points so felt the pressure to get all the cases correct. The time seemed to go so quickly in both exams. In the short cases I felt I only just managed to decide on the morphology before time was being called, leaving me to scribble my answer as best I could. The long cases were tricky and microscopy was time consuming. I found myself becoming incredibly unsure of what I knew and struggled to make decisions. I felt it had all gone horribly wrong and couldn’t wait to leave the exam room.

Unsurprisingly when the results were emailed I had failed both of the microscopy papers, but there was a faint hope in that I had passed the written paper. I was dreadfully disappointed and felt I’d let myself and my colleagues down. This really was a difficult exam and I needed to improve, but where had I gone wrong? The exams take place annually and I was determined to do better next time, but Covid ensured it would be a rather long wait for another attempt.

After a considerable wait, I resat all three examination papers. I was unsuccessful again, however, I did manage to improve and passed the long cases as well as the written paper. My Consultant supervisor could not have been more supportive and together with encouragement from my manager, gave me the confidence to try again. I looked in depth into how I had prepared previously and reflected on how I had approached the exam. So what had gone wrong?

Quite simply, panic and overthinking. The environment and situation of the exam is so far removed from normal working practices. I was looking at unfamiliar preparations, staining and looking for ‘a bear in every bush’. I had managed to pass the long case exam, possibly as there was more time to form a judgement. I am stronger at written exams and so found it easier to add information to gain additional marks. My problem was the short cases exam; I was making an error on one (or more) case(s) and did not manage to gain enough extra marks to achieve the pass. What did I need to change? After much reflection and discussion I determined I was in too much of an exam mind-set and had moved away from my normal screening practices. Things I had recognised I had done previously included screening at X20 magnification, not taking each case in isolation and thinking “What if I’m wrong?” so changing my mind. I established I was being too cautious, not trusting my morphology skills and my answers needed to reflect what I truly thought.

So I set about preparing myself for my final attempt. I covered all my previous preparation methods including setting myself mock exams, lots of help from my peers with active discussion and sharing of knowledge. I found the blue books an invaluable resource for reporting systems and up to date immunohistochemistry and molecular knowledge. However what I had come to realise was that it was my exam technique that needed most work. I needed to change something otherwise I was going to get the same result again. All the people around me seemed to have confidence in my ability so I ensured this time I was going to be decisive and focus on each case in turn. I needed to change my pattern of poor technique and I resolved that this time I would not allow myself to think “What if I’m wrong?”, instead it would be “What if I’m right?”.

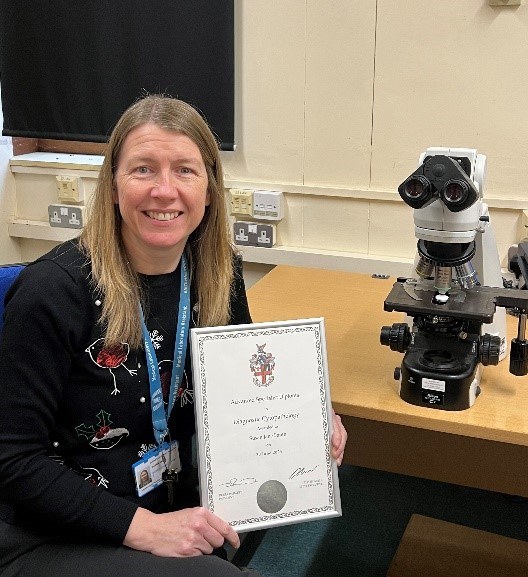

By now I knew what I was letting myself in for with the pressure and intensity of the exams. As per previous times, the cases were challenging and I once again left feeling unsure of whether my decision making had been sound, but I made sure I gave my honest opinion on each and every slide. Results day loomed and I was not hopeful. In actual fact I did not want to know the outcome and endeavoured to put it off for as long as I could. When I finally opened the result email, I genuinely could not believe that I had passed. The relief was substantial; I had done it at last!

So looking back, would I do it again? Yes, I would. But I now recognise that I was not ready the first time I sat the exams. My success has given me significant confidence in my morphology skills; the skills were always there, but doubt and lack of confidence overshadowed them. The exams are very difficult, intentionally so, but there are no trick cases. The portfolio is open and flexible to allow for variations in working practice. The examiners already know candidates can identify overtly benign and malignant changes by virtue of holding the DEP. The exam needs to test how candidates handle cases which are more challenging, for example scanty cells, poorly preserved slides or cases with contradictory clinical information, representative of the real-life scenarios where expert cytopathology skills are essential. When I started I was quite naïve regarding the qualification leading me to be unsuccessful on a number of occasions, but with good preparation and exam technique it is achievable.